Story by Matthew Reed

The one-lane drive threads up a picturesque draw to Belle Hays’ home, past sheep that graze on spring’s new grass.  As I walk up to the slab door with iron band hinges, Belle, a sprightly white-haired woman with cheerful eyes, greets me. She leads me into an expansive living room with slate floors and a domed roof. Bay windows look out on a stone patio, framed in the background by rolling green hills covered in oak and redwood trees. One of the hills, Belle says, they call “Poison Oak Hill.” Looking closer, I can see the thick brush is indeed a mat of tangled poison oak vines.

As I walk up to the slab door with iron band hinges, Belle, a sprightly white-haired woman with cheerful eyes, greets me. She leads me into an expansive living room with slate floors and a domed roof. Bay windows look out on a stone patio, framed in the background by rolling green hills covered in oak and redwood trees. One of the hills, Belle says, they call “Poison Oak Hill.” Looking closer, I can see the thick brush is indeed a mat of tangled poison oak vines.

Belle begins to tell her story.

In 1973, she and John were caring for, among other animals, an abandoned bobcat and a wallaby. They read an article about the keeping of Dexters. Coincidentally, their property in Los Altos was soon to be part of a freeway project. They decided to look for a place where they could raise and breed Dexter cattle, as well as care for the animals they already had. They found forty acres in the heart of the Redwood Empire, previously owned by two “old Finn bachelors.” The main house needed a lot of repair work and became a temporary aviary. Parking a trailer near the proposed location of their new house, the couple set about contacting organizations and breeders of Dexters while John continued commuting to work as an attorney in San Francisco.

In 1974, John and Belle obtained four Dexter cows from a herd in Indiana and a Dexter bull from Texas A&M. The following year, their first calves were born. In order to register their Dexters, the Hayses were required to have a name for their farm. John suggested “Talisman” because their farm was small and so were the cattle they were ranching. According to the American Dexter Cattle Association, sixty-six Dexters were registered under the “Talisman” herd name over time. Belle told me that two dozen head was probably the largest their herd ever was; the rest were sold as they were old enough. Talisman Farm soon began to establish a reputation for breeding quality Dexters.

John became a key player in the reorganization of the group originally known as “American Kerry and Dexter Club,” incorporated in 1943. John wrote the Articles of Incorporation for the new American Dexter Cattle Association in January of 1978. He also wrote the original bylaws for the ADCA, updating the bylaws from 1977 until 1989, and acted as director for the original Pacific Region. John compiled the information for the first edition of Dexter Cattle, commissioned by the ADCA and published in 1984. Currently, Dexter Cattle is in its fourth printing. In 1994, the ADCA made John and Belle Honorary Lifetime members.

The Dexter is the smallest of domesticated cattle. Three-year-old bulls usually do not weigh more than a thousand pounds; they are often less than forty-four inches in height, but are never shorter than thirty-eight inches at the shoulder. Mature cows often weigh 750 pounds; they do not exceed forty-two inches in height, but stand no less than thirty-six inches in height. The two remaining Dexter cows at Talisman Farm that I saw were in fact quite short. I had seen some breeds of domesticated dogs reach heights only slightly shorter than a Dexter. In fact, Belle’s Irish wolfhound seemed to my eye to be as tall as the two small cows. With their bulk, however, Dexters most definitely outweigh any canine. I could see that the pair was still well proportioned and looked quite sturdy, capable of doing any work needed on a farm.

The origin of Dexter cattle is somewhat obscure and debated among Dexter enthusiasts. Some say that a “Mister Dexter,” an agent of Lord Howarden of Tipperary, is responsible for developing the diminutive cattle from the best of the hardy mountain cattle of the region, including the Kerry breed, during the 1750s. This theory of the origin of Dexter cattle seems to have some merit: even today, some of the cattle tend to resemble the long-legged Kerry type, as opposed to the shorter, thicker, “true” Dexter. Breeders agree, though, that the original home of Dexter cattle was the southern part of Ireland where small stockholders bred them in the rugged mountainous regions.

Because of this tough ancestry, Dexters are exceptionally hardy, grazing on poor land where there is only weeds, brush, or leaves, in contrast to standard cattle, which require large tracts of grassy land. In South Africa, ranchers keep large herds for beef production where traditionally only sheep have been ranched. Sheep farmers also use Dexters to suckle as many as eight to ten orphan lambs per cow.

The first recorded importation of Dexters to America was between 1905 and 1915 and numbered over two hundred head. Popular with settlers, the Dexter was an ideal homestead cow, providing milk, meat, and muscle power, but as milk and meat production became more specialized in other cattle breeds, Dexters declined in population to fewer than five thousand in the world. Today, with renewed interest in small holdings, that number has risen to approximately fifteen thousand head worldwide. The ADCA has nearly 650 members and registered 852 cattle in the year 2000, and, according to Wes Patton, president of the Purebred Dexter Cattle Association (PDCA), there are currently five to six thousand Dexters in the United States.

I mention the Dexters’ history as homestead cattle to Belle. “Oh, yes. Women can handle them easily,” she states. “That way the wives could do all the work with the cows.”

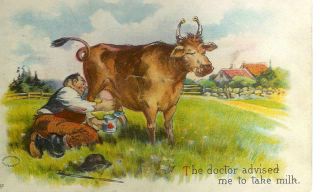

Dexter cattle produce enough milk for most families. Actual milk production varies with breeding and feed, but averages one to three gallons per day. Some owners share the milk with a calf, while others take all of it for their family to use. In every case the owners were pleased with the quantity and quality of the milk from their Dexters.

Wes Patton, of the PDCA, wrote to me saying, “Milk and meat production statistics are not kept by any organization in the U.S. at this time as they are with other cattle breeds. Dexters number so few in herds and total numbers that it is very difficult to gather factual information. Those few that milk them can give testimony as to the level of milk production, but it isn’t well documented. Those that process them for meat can relate all of the virtues of this breed, but again, little has been recorded in a factual manner. I did compare a few Dexters to conventional beef breeds a few years ago as far as feedlot performance and carcass characteristics were concerned, but it was a very small sample. The one thing that did come from that was that Dexters are quite tender when put to a Warner-Bratzler Shear test. Those who have consumed the meat will attest to this too. Average daily gain was in the 1.8–2 pound range, which is in line with their size compared to larger breeds that gain two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half pounds per day. Since they are a dual-purpose breed, the dairy portion of their background results in dressing percentages about 2 percent lower than regular beef breeds, but that is certainly made up in meat quality.”

When I asked Belle if she and her late husband had ever slaughtered any of their cattle, she told me that they had three times had somebody come out and butcher a Dexter. “But it’s so hard to eat them after you get to know them,” she said.

According to John Hays in Dexter Cattle, “an ox is merely a steer with a good education.” Dexters are intelligent, which means that they can pick up bad habits as quickly as good habits. This is not a problem as long as the ox teamster is always smarter than the oxen. Consistency, fairness, and patience are important values, Hays writes, when training cattle. The calves should start to be handled and trained within days of birth. Halter breaking, voice commands, and learning to wear a yoke usually begin early as well. Then, as with many things, it’s all about time and practice.

Dexters’ spunky nature makes them want to pull and do the work asked of them. The larger ones are able to pull a walking plow, logs, and wagons. For the smaller steers, loads have to be scaled down. Putting lots of time into training a yoke of oxen makes any teamster want the pair to last for years. Dexters can be long-lived, another plus for them as oxen. For the competitive ox puller, Dexters can compete in the lower weight classes for their entire lives, an advantage over younger, less experienced yokes of cattle.

Talisman Farm no longer commercially breeds Dexters. John passed away in November of 2004 at the age of ninety-two. The original farmhouse that once served as a temporary aviary is now home to Eric Burtleson, who assists Belle with maintenance of the property and the care of the animals.

“I originally did all the work around here,” Belle says.

Belle tells me Miss Muffet, the nineteen-year-old cow, had originally been sold to a mobile petting zoo, whose insurance company had required the removal of her horns, much to Belle’s disappointment. The other cow, Misty, is younger at sixteen and retains her distinctive horns.

One of the only drawbacks I learned about the Dexter is achondroplasia, a congenital condition commonly called “bulldog.” A bulldog calf is always premature and stillborn. The disease is a form of dwarfism, the recessive characteristic that makes Dexters smaller than average cattle. Achondroplasia often appears when a short-legged cow is bred with a short-legged bull. Breeders now often test for the gene. Belle says she and John had few bulldog problems because they bred only the medium-legged Dexter.

Often, Dexters are separated into two styles or types: the short-legged “true” type and the longer-legged Kerry. The Kerry type is rangier and less compact, but both types are “true” as far as pedigree is concerned. Still, Belle is adamant when she says that the true Dexter is a medium-legged animal with the horns intact. John was equally clear in his book that while dehorning is acceptable in the ADCA standards, a dehorned animal is the lowest in herd pecking order.

Dexters are all black, red, or dun (a dull reddish brown); red, a recessive genetic trait, is a darker, richer hue comparable to that of an Irish setter. Red and dun are only phases of black.

As I speak with Belle, we move outside to the stone patio where I can see more of her farm. A large aviary, first built to contain their wallaby, containing a couple of dozen canaries and a pair of white peafowl sits at the foot of Poison Oak Hill. There is a second, smaller aviary that is home to blue ring-neck and Bourkes parakeets. A handful of white-tailed deer are grazing, and wild turkeys scratch and peck for lunch. One particularly large tom puts on a fine show of his tail feathers for the hens. Almost as if reminded of the time of year, the white peacock in the aviary begins a similar display. Belle says the white peacock tries to win the affections of the peahen every year, but to no avail. Still, his display is grand.

Later, wondering about the actual meaning of “talisman,” I read that a talisman is “something that produces extraordinary or apparently magical or miraculous effects.” The name, then, is quite apt. There is magic in the hills of Comptche, and there live the extraordinary creatures called Dexters.